On March 8th Julie Ann Godson gave a talk on Memories of the Vale before the Railways . The source material came from two books edited by Julie: Memories of the Vale by Rev. Lewin George Main and The Scouring of The White Horse by Uffington born Thomas Hughes, the author of Tom Brown’s Schooldays.

Lewin Main (1828-1897) was curate in Stanford in the Vale from 1859 until 1866 when he became Vicar of St Lawrence Church Reading. He was a town person at heart and had started his professional life as a bank clerk in London. Observation of local poverty moved him to join the church and on completion of his training, he was sent, to his surprise, to the Vale. His first impressions on moving into the Rectory with his wife were not favourable. He observed dilapidated buildings, poorly dressed and downtrodden workers and a relatively primitive way of life in all the local villages. Nevertheless he enjoyed access to all the local families and set about collecting a rich variety of memories and folk lore going back many years, which he described in his book. He regretted the loss of traditional farm clothing of men’s white smocks and women’s bright red cloaks, many of which were family heirlooms.

Main described the daily round of work on the farms starting with the gathering of all the village cattle, summoned by the sound of a cow’s horn at dawn. The main meal of the day was taken at 11.30 and tea in the farmhouses was taken at 3.30.Transport was dominated by horses and every village had a blacksmith. Older farmers still remembered manure being taken to the fields in large baskets carried by horses. They also remembered the dog whipper, paid four shillings a year to keep the large number of strays out of the village church. Village games and pastimes remembered included cock fighting, hockey, skating in winter, marbles and the occasional fox hunt. Churchwardens’ records gave details of charitable work at Whitsun to raise funds for the poor, including the sale of ale in the church, regarded by some as a pagan practice. Local dialect interested Lewin Main and he concluded that in the Vale it was predominantly of pure Anglo Saxon origin. An example cited was the word for a new year gift: a hansel. He also noted that in the years after the civil war Christian names changed dramatically and those based on Old Testament characters became much favoured.

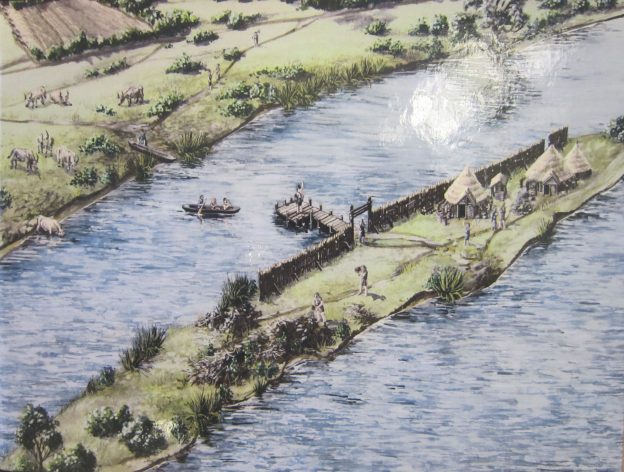

In the second book edited by our speaker, Thomas Hughes described the history and practice of the annual refurbishment of the White Horse known as Scouring. Villagers and visitors would gather to clean the chalk monument, thought in those days to be associated with King Alfred and his wars with the Danes. We now know it was constructed in the bronze age. The local squire provided food and drink for the workers including two eighteen gallon barrels of ale. The event was also embellished by many sporting activities known as ‘The Pastime’ to which as many as twenty thousand visitors were attracted. Local men complained that men from Somerset had an unfair advantage in the boxing because they had less blood in their heads as a result of excessive cider consumption!

In conclusion Julie Ann told us that the Rev. Main had a somewhat ignominious change of career when he and his wife suddenly fled to Yorkshire in 1874 following a ‘domestic affliction’. When Mrs Main died twenty years later Lewin was joined by the governess from his Reading vicarage and they lived together until his death three years later. She lived on until 1936 when she died aged eighty nine.