Medicine in Oxford from the 13th to the 21st Century On Thursday 9th February, the History Society heard a fascinating talk by Victoria Bentata on the subject of Medicine in Oxford from the 13th century onwards.

She started with the legend of St Frideswide, whose well in Binsey was said to have healing properties. In Medieval times Science and Religion were very closely linked.

But the first true scientist was Roger Bacon, in the 13th century. He was a Franciscan Friar whose ways of thought were very much ahead of his time. He believed in the importance of experimentation in pursuit of his studies. This approach has relevance today.

The next important figure was John of Gaddesdon, member of Merton College and Doctor of Physik in Oxford, who lived into the 14th century, and was probably the model for Chaucer’s Doctour of Phisik in the Canterbury Tales. He wrote a treatise on Medicine, called Rosa Medicinae, which was widely read, and drew largely on Greek sources.

In the 15/16th Centuries one of the most important Oxford figures was Thomas Linacre. He doesn’t seem to have practised medicine while in Oxford, but later he practised at the Court of Henry VIII, and was one of the founders of the Royal College of Physicians.

Robert Burton, born in 1577, an eminent scholar from Brasenose College, specialised in “Melancholy”, and indeed wrote from personal experience. His treatise on “The Anatomy of Melancholy” was very widely read, But he himself suffered from depression, and is said to have hanged himself in Christ Church.

In the 17th Century, there appeared a group of academics, under the name of the “Oxford Philosophical Society”, led by John Wilkins, Warden of Wadham College. They were very active, conducting many experiments in Wadham College gardens.

William Harvey (b.1578), who was the first to discover and describe the circulation of blood in the body, also became Royal Physician to King Charles the 1st, and 1 accompanied him to Oxford, where he stayed until the city’s surrender to the Parliamentary forces.

Thomas Sydenham (b. 1624) might be regarded as the English Hippocrates, or as the father of English Medicine. He wrote on the best way of treating patients, but he also worked on a drug to cure malaria, among other things.

Thomas Willis (b. 1621) was an early neurologist who performed many dissections, and was a founder member of the Royal Society. His home in Oxford was opposite Merton College, and was notorious for the smells of decaying bodies emerging from it. He worked with the future Architect Christopher Wren, who made a drawing of the human Brain from one of Willis’s dissections. Hogarth, too, included scenes of dissections in his pictures.

Connected with Thomas Willis was the story of Anne Green, who was convicted of the murder of her baby (born after she had been raped), and sentenced to death. The execution was carried out, but the next day she was discovered to be still breathing. Several doctors including Willis set about reviving her, and they were successful. She was pardoned – her revival was seen as an act of God. Later, she married and eventually had three children.

Dr John Radcliffe (b. 1652) graduated from University College, Oxford, eventually became Royal Physician to William and Mary, and became a very rich man. He was said to be an outstanding diagnostician, hence able to choose patients whom he expected to survive – so he enjoyed a very good success rate. When he died he left an enormous fortune, most of which went to charity, and to developments in Oxford such as the Radcliffe Camera and the Radcliffe Infirmary.

Henry Acland (b. 1815) was a life-long friend of John Ruskin, and helped to found the Oxford Natural History Museum. He made a study of the Cholera outbreak in Oxford in 1854, and explored ways of caring for the poor.

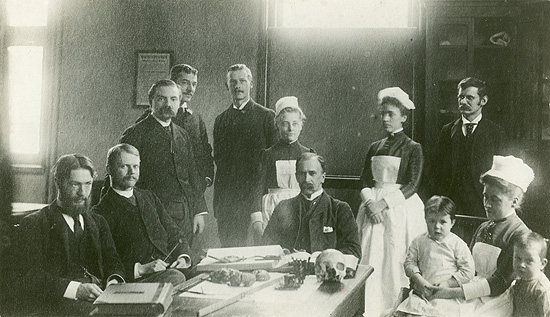

William Osler (b. 1849) was a Canadian who spent his early life in Baltimore at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. He developed a patient-centred way of working, advising doctors to ‘listen to the patient, who will tell you the diagnosis”. He was appointed Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford in 1905, and soon met the young William 2 Morris, who repaired his Renault car. This was the beginning of a long friendship between them. As a result, Morris (Lord Nuffield) endowed 5 new professorships, and created the Iron Lung which he distributed to every hospital in Britain.

Hugh Cairns (b. 1896) was born in South Australia, and came to Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. He became the first Nuffield Professor of Surgery, and treated T.E.Lawrence after his motorbike accident. As a result of that, he designed a motorcyclist crash helmet, which was used by despatch riders during the War, and he treated 13,000 servicemen.

Sir Ludwig ‘Poppa’ Guttmann (b. 1899) Although he was a Jew, he was ordered by Hitler to go to Portugal to treat a friend of the Dictator Salazar. Afterwards he came straight to the UK, where he settled in Oxford and carried on his research in Neurosurgery. Later, he worked at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, and was a leading force in the development of the Paralympics.

Howard Florey (b. 1898) and Penicillin. With his team, he worked on research into Penicillin, and treated his first human patient (an Oxford policeman) in 1941. By DDay enough penicillin was being produced to use on wounded soldiers. Florey refused to patent Penicillin, or to talk to the Press. A Memorial to the work of the Laboratory is in the Rose Garden in Oxford Botanic Garden.

Dorothy Hodgkin (b.1910) in 1945 she solved the structure of Penicillin.

Richard Doll (b.1912) Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford. He made an important study of the effects of Smoking and its connection with Cancer, and revolutionised the organisation of the OU Medical School.

Joshua Silver developed the self-refracting glasses, which enable patients everywhere to benefit from glasses, whether there’s an optician near or not.